The topics of Curiosity, Creativity and Innovation have seen increased press over the past several weeks as businesses, governments and individuals respond to the challenges posed by the Novel Coronavirus. And if you’ve been following the business press for the past decade or so, you are well aware that these are not new topics. However, from a broad-based perspective, the need has never been more real.

Unfortunately, there is a global shortage of leaders with creativity and innovation competencies. The deficiency we currently face – as it relates to curiosity, creativity and innovation in business – is in part due to our educational system and legacy business management thinking.

As Gary Hamel (London Business School) states in a recent Irish Times interview:

“Every major company in the world has re-engineered its operating model for speed and agility with enormous investments in back office and optimizing supply chains but that’s not enough. Now we need to re-engineer the management model for innovation. How do we hire, how do we compensate, how do we allocate resources, how do we plan, are questions we need to ask but most importantly we need to know, what do we do here that frustrates innovation?”

Let’s face it, management has largely been thought of as an approach for controlling people and processes. And as a result, over the past several decades we seen many companies maniacally focused on inward-looking “efficiency” (aka – cost containment) initiatives. The benefits of Continuous Improvement (CI), Total Quality Management (TQM) initiatives are undeniable. But as these initiatives approach maturation (meaning the lion’s share of the benefits have already been harvested), executives need to be seeking a more balanced approach, whereby leveraging CI/TQM in conjunction with a renewed focus on top line growth.

The issue, as Hamel points out, is that the management and leadership skills needed to implement and execute CI or TQM programs don’t necessarily lend themselves to innovative top line growth. To be clear, innovation is the engine of organic top line growth; and today’s businesses desperately want and need talent with innovation skills and competencies.

As I noted earlier, the current pandemic crisis is shining a renewed light on the need for, and value of creativity and innovation. And while there is a lot of buzz around these topics, I actually feel there is a fair amount of confusion, or at least a lack of clarity about what the terms Curiosity, Creativity and Innovation actually mean.

For the balance of this piece I will take a look at what business leaders mean when they use these terms and how that can vary from what people think they mean, and what they actually mean. My hope is that the following discussion will provide some useful understanding and valuable insight to these important topics.

Creativity wanted:

In their 20th CEO survey, researchers from PwC found that innovation was most widely cited as a CEO’s number one priority; and 77 percent of the participating CEOs claimed that their organizations struggle to find the creativity and innovation skills they need.

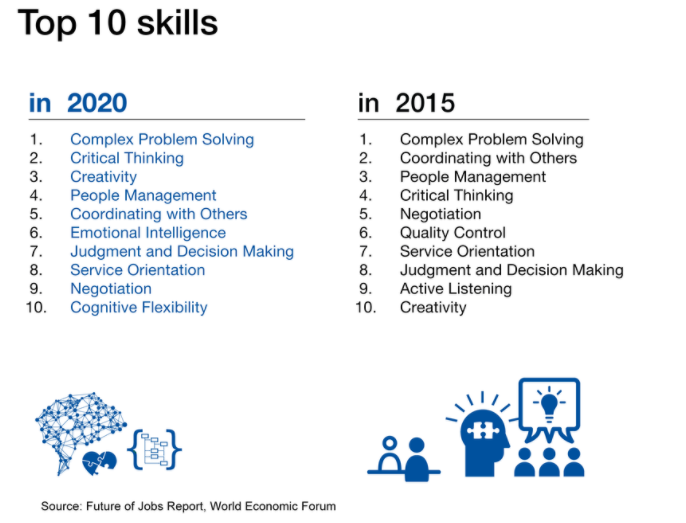

Additionally, a 2016 report from the World Economic Forum predicted that creativity would be one of the most needed skills in the workplace by 2020.

And what’s most interesting to me about the WEF findings is that I feel “Complex Problem Solving”, “Critical Thinking”, “Creativity”, “Judgement & Decision Making”, and “Cognitive Flexibility” are all related to each other. Right?

Maybe it’s just me…

The more I thought about these findings from these reports, the more something just kept nudging at me. But I wasn’t sure why I kept thinking about this. Something had definitely piqued my curiosity though. Finally, it dawned on me; the thing that was gnawing at me was my own lack of clarity about what creativity really was. And for that matter, why was I even curious about this in the first place?

Curiosity

OK admit it, like me, you’ve probably never really spent much time thinking about what curiosity actually means. Which I guess is a bit ironic given that I tend to think of myself as being a naturally curious individual. It’s just one of those words I’ve used over the years, without much serious thought regarding its true meaning.

So, what is curiosity?

Generally, I feel curiosity is about inquisitiveness, or a desire to understand, or even a drive to learn. Curiosity does strike me however as something that is internal or innate. Put another way, curiosity is something that… is just there. However, due to the motivation of my nudge, I began to wade into some research on “curiosity” – and it wasn’t long however before I took a full-on swim in the ocean. Perhaps a side effect of be being curious…

Curiosity, as it turns out, has long been a subject of inquiry and study with references dating back prior to the times of Aristotle. George Loewenstein (Carnegie Mellon) in his article “The Psychology of Curiosity” (Psychological Bulletin, 1994), starts out by stating that “curiosity has been consistently recognized as a critical motive that influences behavior in both positive and negative ways at all stages of the life cycle.” Jerome Kagan (Harvard) in his article “Motives and Development” (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1972) describes curiosity as the “motive for cognitive harmony”, or “the need to know.” Thomas Gilovich (Cornell) in his book “How we know what isn’t so” (Free Press: 1993) states that humans “are predisposed to see order, pattern and meaning in the world and we find randomness, chaos and meaninglessness unsatisfying.”

And I absolutely love how Clarence Leuba (Antioch College) in his article “A new look at curiosity and creativity” (The Journal of Higher Education, 1958), underscores now how innate curiosity really is by stating that “examining, investigating and exploring – [are things] we label curiosity, and they are very evident as far down the animal scale as the rat and perhaps even farther.” So, curiosity is actually something that is just there – not only in humans, but also in animals.

After synthesizing all of this, I’ve come to the point where I think about this trait in terms of one’s pursuit of utility in an intrinsic, economic-decisioning framework. That is, we naturally seek benefits derived from exploring, discovering and understanding. It’s a part of how we’re wired. I also feel the instinctive utility from curiosity is driven by two motives or pathways.

The first motivation pathway of curiosity is associated with a nature’s primal defense mechanisms – more instinctively driven. This curiosity’s utility is protection and safety. It is preventative in nature and is a preparatory device for coping with and/or avoiding adverse outcomes to external changes.

Curiosity’s second motivation pathway is more proactive and prospective. It is exploratory and seeking in nature. And while there may be traces of the first motivation pathway underlying the second, I feel this pathway is quite different. The curiosity utility derived from this pathway is expansionary. The motivation is the prospect of some “gain” to be had by knowing more through examining, investigating, exploring and discovering. I consider this to be a higher-order level of curiosity – which has greater linkage to creativity – and more along the lines of what business leaders are seeking. And while this higher-order level of curiosity is a necessary ingredient for creativity, it is not sufficient in and of itself.

Creativity

I’ve tended to think about creativity as a trait (i.e., she has an amazing amount of creativity), as well as a process – (i.e., that widget is the result of a lot of creativity). And according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, creativity is “the quality of being creative or the ability to create.”

However, I’ve always had an issue with having to use a word in its own definition.

But, Robert Franken in Human Motivation (Wadsworth Publishing, 2006) does it brilliantly in my estimation. He defines creativity as “the tendency to generate or recognize ideas, alternatives, or possibilities that may be useful in solving problems, communicating with others, and entertaining ourselves and others.” How cool is that!

Thus, creativity the trait involves one’s abilities to perceive, assemble, synthesize, envision, generate and leverage stimuli and ideas in unique ways. And as I noted earlier, Creativity is also a process.

Creativity the process

The creative process, as originally detailed by Graham Wallas in “The Art of Thought” (Harcourt, Brace, 1926) entails four steps:

- Preparation – Time spent actively learning, synthesizing and hypothesizing

- Incubation – Time spent disengaged but subconsciously processing

- Illumination – The aha moment

- Verification – Testing, refining and finalizing the solution

The “father of creativity” E. Paul Torrance, in his article “Understanding Creativity: Where to Start?” (Psychological Inquiry, 1993) expands upon Wallas’ above notion of ‘creativity as a process,’ as follows:

“First, there is a sensing of a need or deficiency, random exploration, and a clarification or pinning down of the problem. Then ensues a period of preparation accompanied by reading, discussing, exploring, and formulating many possible solutions and then critically analyzing these solutions for advantages and disadvantages. Out of this comes the birth of a new idea – a flash of light, illumination. Last, there is experimentation to evaluate the most promising solution for eventual selection and perfection of the idea.”

Torrance goes on to explain that the potential outcomes of this process could be the creation of new, novel or improved things ranging from ideas, to works of art, to physical items and processes. In other words, the Creative Process may lead to an innovation! In fact, the creative process is very much how people describe various steps of the innovation process. Much in the same way that curiosity is a necessary ingredient for creativity, Creativity is a necessary (but not sufficient) ingredient for innovation.

Innovation

So, what is innovation? Similar to creativity, Innovation has two meanings. That is, it is a thing, as well as a process. While innovation has been showing up in the media left and right for more than a decade, there is still a lot of confusion about what innovation actually is and how it happens.

Innovation is the process of creating and delivering new, and differentiated consumer value in the marketplace, which can create a competitive advantage.

In order to create an innovation (a new thing which creates new consumer value), you have to employ the process of innovation. I think most will stipulate to the notion that innovation is an engine of economic (business) growth, and that it can create a competitive advantage, so I won’t spend time belaboring these points. I do however want to conclude by discussing the process of innovation.

In an article I wrote a while ago entitled “Continuous Innovation and Continuous Improvement,” I outlined my approach to the innovation process as containing the three following phases:

- Identify – Find opportunities for new products or services based on unmet or underserved consumer needs

- Innovate – Create new products or services using an iterative pilot / minimum viable product (MVP) test and learn approach

- Implement – Adopt the solution, rollout, scale, monitor and refine.

In order to successfully create a new innovative product, service, process or business model, that produces new consumer value, one must employ each and all of these phases.

If one were only to identify an opportunity (phase one), they’ve exhibited curiosity and some steps of the creative process previously noted. But all they would have at this point is a thoughtful (maybe even really cool) idea. That is it! An idea however is not innovation.

If one were to identify an opportunity and create a prototype in their garage and stop there (phases one and two), they’ve exhibited curiosity and all of the steps in the creative process. They perhaps might even have something that could be considered an invention; but they’ve not created any consumer value at this point. There are tens of thousands of patented inventions, that produce zero consumer value. For something to be an innovation, it must create new consumer value in the marketplace.

To create value through innovation, an unmet need has to exist, the right solution (product, service, etc.) needs to be devised, it needs to be developed, produced or launched, and it needs to be made available to the marketplace; where it is purchased and repurchased due to consumer demand. It is only after the creation of consumer value however that we can say we truly have innovation. And, not coincidentally as we’ve already pointed out, we also have benefitted from curiosity and creativity.

This then brings me back to my original assertion. The need for Curiosity, Creativity and Innovation couldn’t get much higher as our global society faces a once in a lifetime health crisis. And I really like how McKinsey underscores the current need:

“The extraordinary constraints and imperatives brought on by the COVID-19 crisis have rapidly thrust businesses into challenges they could never have envisioned. Many have had to innovate new capabilities for remote operation almost overnight, complete digital transformations in weeks rather than months or years, and launch new products in a matter of days. We believe the COVID-19 crisis will be a period of substantial business building and innovation.”

For organizations who are already wired for innovation, the current crisis has forced an unplanned pivot; but they already have the chops and processes to successfully make the adjustment. However, if your organization has lost its innovation mojo, you’re acutely aware that the demand for Curiosity, Creativity and Innovation couldn’t be more pressing. My advice to you is this – keep in mind that your organization was likely created as a result of Curiosity, Creativity and Innovation. Get back to your innovative roots and tackle this external disruption.

Leave a Reply